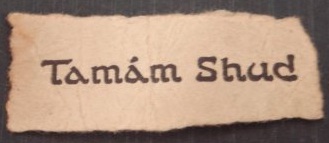

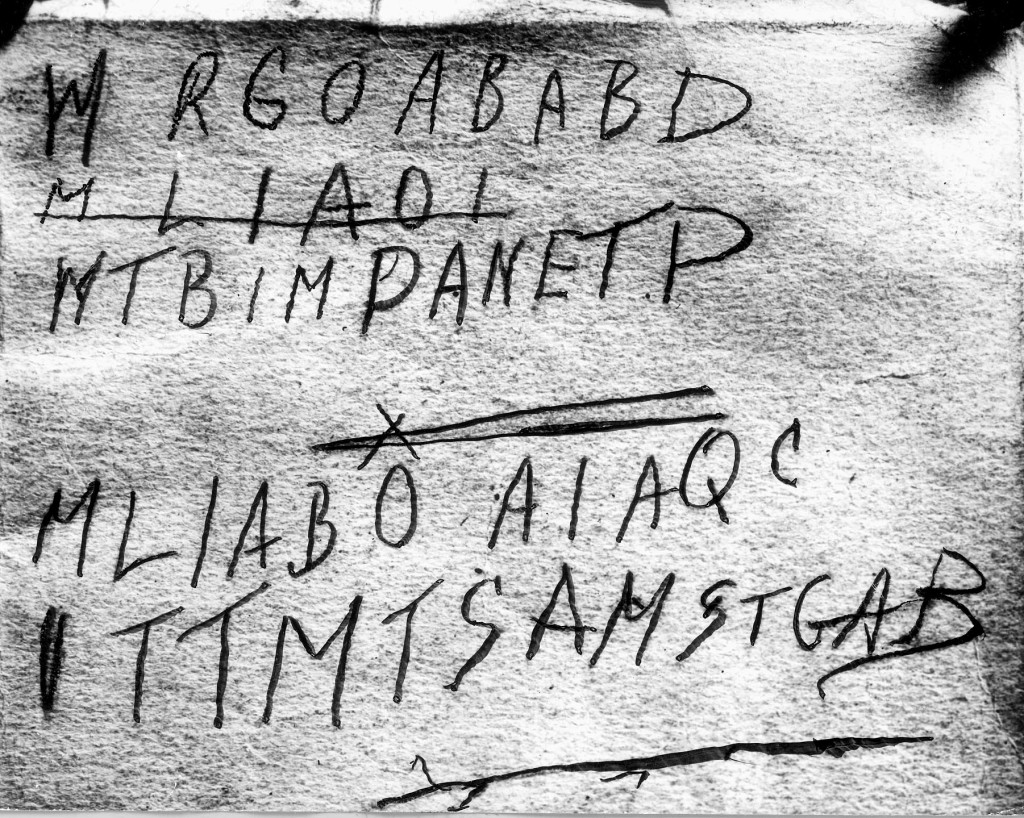

Early in the morning of 1st December 1948, a man was found dead on Somerton Beach in South Australia, not far from Adelaide. His body had no wallet, no ID card or other means of identification, and has remained unidentified throughout the more than six decades since.

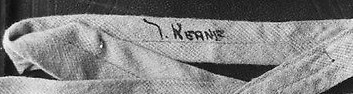

A couple of weeks later, police managed to connect a suitcase that had been left in Adelaide Railway Station to the dead man, thanks to an unusual kind of thread: but here too hardly any of the contents had any names written on them. The three items that did read “Kean”, “Kean” and “T. Keane”, but despite extensive searching at the time, nobody with that name was ever found to have gone missing.

Then, a scrap of paper was found rolled up and tucked away into the fob pocket in the dead man’s trousers: it said “Tamam Shud”, which means ‘the end’ – it is the last two words of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a book of verse that was very popular at the time.

Bizarrely, police managed to link this tiny scrap of paper with a copy of the Rubaiyat that had been left inside a (today still unnamed) stranger’s car in Glenelg around or before the date of the mysterious man’s death. (Specifically, the car owner recalled that he had discovered the copy around the time of the RAAF Air Display at Parafield near Adelaide, on 20th November 1948.)

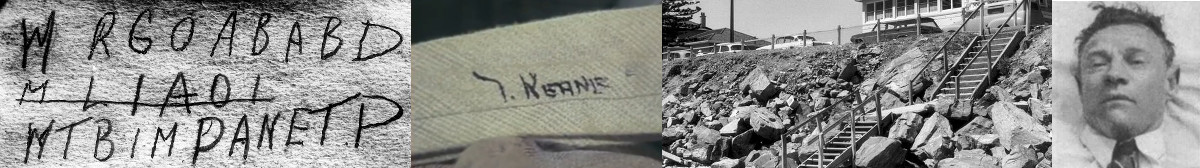

And finally, police discovered (from indentations that showed up under police photographers’ infra-red lights) that an unexpected message just happened to have been written on the end page of that copy of the Rubaiyat:

This curious message was quickly sent to be analyzed, almost certainly to Captain Eric Nave (who was the best and most highly-accomplished code-breaker in Australia). Nave concluded that, because the letters had a very similar instance frequency distribution to that of the first letters of English words, it was very probably that the text was an acrostic cryptogram, formed from the initial letters of some English phrase or message, possibly even a poem.

However, nobody has made any significant progress since then. Despite the efforts of hundreds of armchair cold case sleuths and sofa code crackers, the Somerton Man remains unidentified right to the present day.

The Nurse

One other unexpected line of enquiry presented itself at the time.

In addition to the mysterious cipher-like writing on the end page, police also discovered one or two phone numbers there. One – “X3239” – was that of a local nurse, Jessica Ellen Thomson (née Harkness), who lived close by at 90A Glenelg Street. Unsurprisingly, this has led over the years to little short of a barrage of conspiracy theories and attempted romantic / etc explanations, none of which has yet proved fruitful in any obvious way.

Up until her death in 2005, Harkness / Thomson denied all knowledge of the man’s identity: but in 2014, her family revealed in a TV documentary that she had said that she did know who the dead man was. All the same, we still have no clue of his actual identity, because she never revealed it to them either.

And so the mystery goes on.

Evidence

* ABC Inside Story documentary, episode “The Somerton Beach Mystery”, first screened Thursday, August 24th, 1978 (now on YouTube): Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

* Professor Derek Abbott’s primary evidence page. This includes inquest reports, etc.

* Professor Derek Abbot’s secondary evidence page. This includes newspaper reports, transcripts, other material, etc.

* The best book on the Somerton Man / Tamam Shud mystery is Gerry Feltus’ detailed (2010) The Unknown Man.

Evidence Questions

* Does the Army or the Navy still have a copy of the photograph from which the above image was taken?

* Does the family of SAPOL police photographer Jimmy Durham (who worked on this case) have copies of any of his photographs?